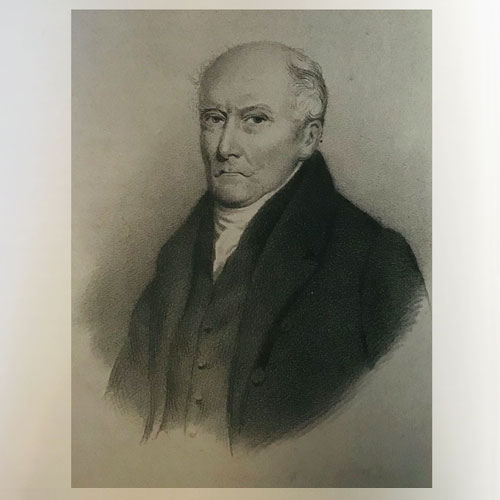

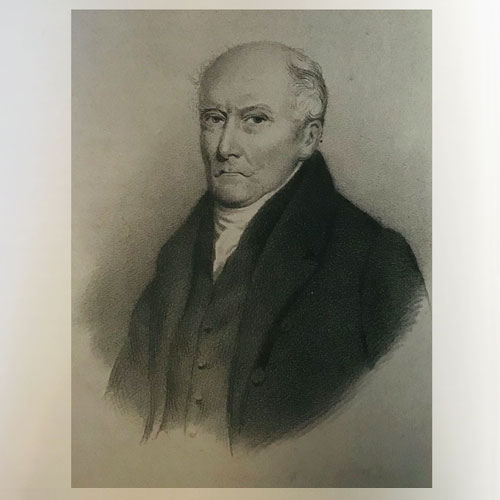

Daniel, Thomas (1762–1854), merchant, was born in Barbados on 16 September 1762, the son of Thomas Daniel (1730–1802) and his wife, Eleanor, née Neil (1737–1774). He was the fourth generation of the Daniel family to be born on the island since his great-grandfather John Daniel (1623–1689) had emigrated there from England in the mid-seventeenth century. In 1764 Thomas Daniel senior took his family (including the two-year-old Thomas junior) back to Bristol and established himself there as the fifth largest sugar importer in the city before 1800. A prominent headstone in Bristol Cathedral honouring the elder Daniel attests to the Barbadian origins of this ‘respectable merchant’.

As his father's main heir, Thomas Daniel junior, who had lost his mother at the age of twelve, built upon and diversified the family's business empire and came to exert increasing control of Bristol's political establishment. He became a freeman of the city in 1783 and despite his youth was elected as a member of Bristol's common council in 1785 becoming sheriff of Bristol in 1786–7. His marriage in 1789 to Susanna Cave (1767–1846), the daughter of John Cave, a Bristol apothecary and later banker, further cemented his links with Bristol's mercantile élite. In 1782 he became a founding member of the city's West India Committee and soon became a leading member of Bristol's Society of Merchant Venturers who controlled foreign trade and much else besides in the city. As both a merchant venturer and member of the West India Committee, he sought to safeguard the interests of planters and all those dependent on the West India trade. As such he became a formidable opponent of both the abolition of the slave trade and the emancipation of enslaved Africans in the British Caribbean where he and his family owned plantations. By 1796 he had become an alderman (a post he retained for over three decades), and the following year, 1797, he was mayor of Bristol. A staunch Anglican and tory, he actively opposed Catholic emancipation and parliamentary reform. His wider civic involvement included the presidency of Bristol's Colston Society, the Gloucestershire Society, the Dolphin Society, and (in 1807, 1815, and 1816) membership of the exclusive Tory Steadfast Society. He was governor too of Bristol's Incorporation of the Poor, a sponsor of the Prudent Man's Bank, and treasurer of both the Red Maids' School and Queen Elizabeth Hospital, educational institutions with a long pedigree in the city. Instrumental in wresting control of Bristol's corporation from the whigs by 1812, Daniel was an assured political operator and his ‘complete omnipotence in corporation affairs’ reportedly earned him the sobriquet of ‘the king of Bristol’ (Latimer, Annals of Bristol in the Eighteenth Century, 455).

The range and extent of Daniel's business interests in both Bristol (as Thomas Daniel & Sons) and London, where he was in partnership with his brother John Daniel (1768–1853) as Thomas Daniel & Co., were equally impressive. Aside from sugar importing and sugar brokering, he was, by the turn of the century, embedded in a variety of enterprises including iron importing from Sweden (as Daniel, Harford, Weare, and Payne), banking (as a partner in his father in law's firm Ames, Cave & Co. between 1801 and 1821), and also had shares in the Bristol Copper Company and local coal mines (in nearby Bedminster)—most of which were related in one way or another to the sugar trade and sugar refining. By 1803 he was listed as a leading investor and director of the Bristol Dock Company as the official representative of the Society of Merchant Venturers (he became master of the society in 1805) and was a director of the Bristol Fire Office. In 1829 Daniel was on the bridge committee which sought designs for an iron suspension bridge from Clifton Down over the River Avon and was named as one of the Clifton suspension bridge's first three trustees in 1830. Daniel's shipping interests—overwhelmingly focused on the West India trade—were extensive. Between 1786 and 1837 Thomas Daniel & Sons had ownership or part ownership in twenty-five ships (including by 1835 a ship called the Thomas Daniel which sailed from Bristol to Madeira and Barbados). His father had already established the family firms as an important creditor and trader in the Caribbean, but under Thomas junior's watch they not only gained control of ‘a sizeable section of the West India trade’, becoming by the 1830s a ‘major force in Barbados and the Windward islands’ (Butler, 66–7), but also established themselves as one of the leading providers of mortgages to Barbadian planters. Between 1823 and 1843, when the mortgages of some fifty-three Barbadian plantations fell into arrears, twelve were in debt to Thomas Daniel's firm which purchased three of them outright.

By the time of emancipation Thomas and John Daniel claimed a financial stake in over three dozen plantations throughout the Caribbean, and compensation for over 6900 enslaved Africans. In total, they submitted 52 claims, of which 27 were successful. When the moneys were finally awarded to successful claimants in 1837, the Daniels received compensation of over £135,000 for more than 4300 enslaved people on some 28 plantations, with Thomas personally receiving additional compensation for 200 people ascribed to him in his own right. This made Thomas Daniel one of the largest beneficiaries of the total £20 million compensation paid to slaveowners. Some of that compensation money may have found its way into Daniel's industrial investments at home. He had by 1835 become a major shareholder in the Great Western Railway. He also invested in land in Bristol, Gloucestershire, and Devon including Stoodleigh Court, Devon; the Stockland estate, near Bristol, which he purchased in 1839; a country residence in Henbury near Bristol; and a townhouse in Berkeley Square, Clifton.

Daniel continued briefly as an alderman after the Municipal Reform Act of 1835 transformed the local corporation into the city council but by 1836 had ceded his role as leader of the local tory faction. Aged seventy-two, he himself admitted that his memory was beginning to fail, and he was pressured to decline the nomination for mayor on the grounds that his position as a member of the Society of Merchant Venturers posed a conflict of interest. In 1838 he continued as a city councillor and was still a presence in Bristol's wider social fabric, as ‘the father of the city’ rather than its king. Before ill health ended his public career in 1841, he was still serving as a founding shareholder in the Bristol, Clifton, and West of England Zoological Society, as a trustee of Dr White's Charity, and as president of both the Horticultural Society and of the Bristol Asylum. With his wife, who predeceased him, he had six daughters, Maria Anne (who died en route to Barbados in 1817), Frances, Susanna, Lucy, Ellen Susan, and Emily, and one son, Thomas (1799–1872), a West India merchant who followed his father into the Society of Merchant Venturers in 1822.

Daniel died of ‘natural decay and sinking of vital powers’ (d. cert.) at his home, 20 Berkeley Square, Clifton, on 6 April 1854, and was buried at St Mary's, Henbury, Gloucestershire. On the demise of ‘this mightiest of our city magnates’ (Bristol Mercury, 8 April 1854) ‘half-masted flags … float[ed] from the Council-house, from other public buildings, and from the shipping in the port’ (Clifton Courant, 12 April 1854). Daniel was the emblem of pre-reform Bristol when the slave-based West India trade underwrote the city's and the nation's prosperity.